Community property states are jurisdictions in which a homeowner can choose to use a property that is shared by the community as opposed to an individual property. Each of these states has some very unique characteristics that set them apart from the others. As you will see, it is important to understand what they are in order to know how to best avoid being negatively impacted by them in the future. Let’s take a closer look at these three states to get an idea of how they work and why you may find yourself in them.

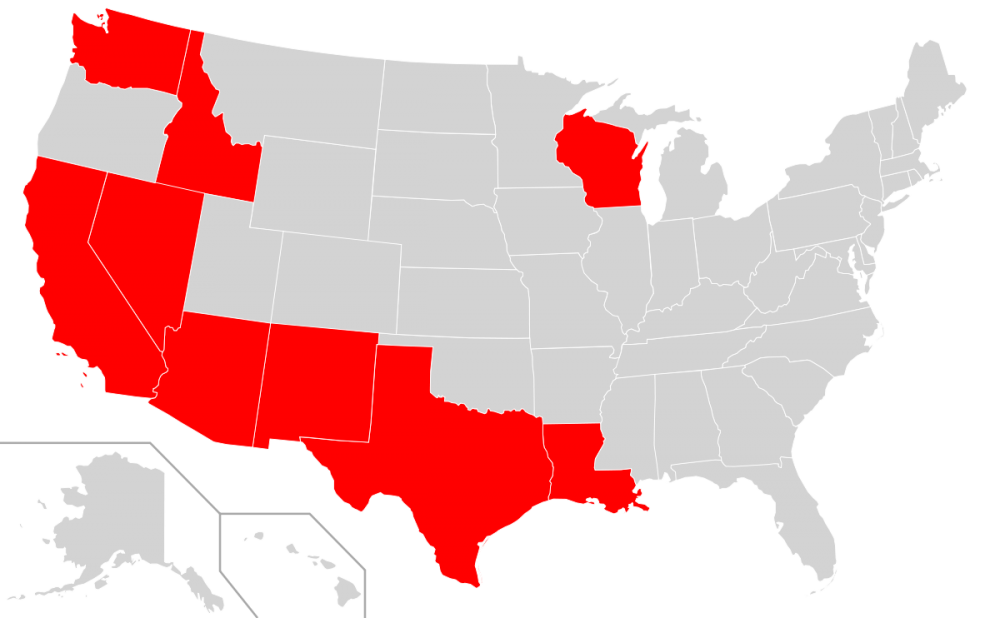

The United States has nine common law states: Alabama, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Kansas, Kentucky, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Oregon, and South Carolina. Additionally, three other states have chosen to implement optional community property states. In addition to those that have chosen to implement their own community property laws, ten states still legally permit both parties to share property. These include Connecticut, Delaware and Rhode Island. (Rhode Island only recognizes a single common law marriage in which both parties are legally married.)

In community property states, whether one spouse owns the other depends on what the community rules say. For example, in some states one spouse may be entitled to all of the assets of the other spouse. In other cases, one spouse may only be entitled to a fraction of the assets of the other spouse. It really depends on the situation, but in most states it is better for the couple to agree on which rules apply to them rather than trying to get away with one spouse’s property and leaving the other out.

In many community property states, one spouse may own real estate and share title with the other, or they may both own real estate and share title. Some states recognize a spousal trust or common law marriage as a true marriage. In these cases, one spouse would be considered an exclusive owner of real estate while the other spouse would be considered the exclusive owner of personal property. If one spouse dies, the surviving spouse would continue to live under the same rules as in a traditional marriage. This could include asset protection for survivors, who will be responsible for the care of any minor children and/or any debts of the deceased spouse that were contributed to the decedent’s estate.

One of the differences between community property states and traditional marriage is the length of time during which one spouse can remain married. In most states, the period of time from the date of separation until the date of marriage is treated as a permanent marriage. Asset acquisition and disposition in community property states are not considered until the date of death. Once the surviving spouse has been given authority to collect a debt or obtain a power of attorney after the death of the other, assets owned during the period of marriage can be transferred without waiting for a court decision at any time.

Assets that are not immediately inherited or that become part of the estate after death may pass under the probate laws of community property states during the life of the decedent. Under these conditions, the surviving spouse or the estate may decide to make an offer under the provisions established by the community property laws. An offer to divide may be made to avoid probate and to eliminate the need for the probate court to issue an order. The amount that can be divided will vary by state and county. The surviving spouse or estate can also file a petition with the court requesting a certificate of probate stating that the decedent was not under the supervision of the courts when he/she died.

It must be noted that probate in Arizona is handled differently than in most other states. If a person dies without having a will in place or having left instructions for funeral and burial arrangements, his/her property will be subject to community property laws. In Arizona, this applies to all property owned by the decedent, including real property, bank accounts, vehicles, jewelry, collectibles, furniture and antiques. There are also a few exclusions to the general rule of community property states. For example, the state may consider vacant land to be community property, as long as the ownership is in writing and the deed does not appear to be contested.

Property held by the surviving spouse or the estate of the first spouse during the decedent’s lifetime is known as community property. However, it is also possible for the property to be individually owned during the decedent’s life and be subject to community property laws. When this occurs, it can be difficult to determine who holds title to the property. Many community property states attempt to simplify this process by granting joint ownership to both the surviving spouse and the estate during the decedent’s life. If there is no will, both the surviving spouse and the estate will be considered owners of the property during the decedent’s life, regardless of whether or not they own the property directly. This provides the opportunity to resolve any title problems that may arise.

Recent Comments